The Coming Ice Age

When I was a child, amongst my favourite books was an old A4 sized hardcover by one Zdenek Burian, on animals of the past. Burian probably illustrated more than five hundred books on palaeontology and evolution, and even now his illustrations - of long-necked saurians, birds out of nightmares and unsettling animal-men - I find unexpectedly moving.

When Burian wrote, the great story of life on earth was simpler. Prehistory progressed, as it seemed history had, via an orderly and inexorable successsion of ages. As in our past we had seen the Age of Stone superseded by the Age of Bronze, and that by the Age of Iron, in Burian's books we saw the Age of Fishes yield to the Age of Reptiles, and that to the Age of Mammals, and finally Man.

There was a mythic quality to these cycles of dominion and overthrow. In each case, the story would be the same. A vast and ancient Empire - the Empire of the Placoderms, the Neanderthals, the Assyrians - would hear rumours of fantastic and terrible beings appearing on the fringes of the Empire. At first these would be dismissed as travellers tales. But with horrible suddenness the strangers would arrive, all would fall into chaos and the old order would be destroyed - making way for the Teleosts, the Cro-magnon Men, the Babylonians.

A powerful, secure-seeming structure to hang a story on, and one which fits more easily in our heads than a lot of others.

And today I heard another young man talking about how everyone's all fucked up on the ice.

Ice, for those of you who don't know, is the crystal form of methamphetamine. Local terminologies vary (as does purity, price, everything), but the basic progression (an amphetamine evolutionary series) could go speed or meth to ice. Anything I say for amphetamines here I say for speed and essentailly the same amount for meth and tenfold for ice.

Ice and its various relatives - and since most of the stuff is not made by qualified analytical chemists, approximations must be made so that when I say "ice" I should be understood as saying "the hodpodge of half-baked industrial chemicals sold by scabby australopithecines with gleaming eyes to teenaged psychotics-in-training as ice" - ice is probably the fastest growing injectable drug franchise in Australia.

Seriously, the young man across from me was saying, it's everywhere. Can't cross the street without someone offering it to you. Down the pub, at the local footy game, when he dropped his kid off to school.

Ice is a very in thing. Ice is not only the new speed (and for the coming generation speed is the new heroin), for a growing number of people it's the new alcohol as well. Go out on the weekend, have a taste. Cheaper than a carton of Carlton Draught, gets you higher and doesn't leave you with a hangover.

But the reason for the young man's concern - and mine - is that ice, even more than the conventional forms of amphetamines, does really bad things to you. It's hard to compare drugs - and any time you do, tobacco ends up so far ahead, so much further along any axis of evil you care to use - it's hard to compare drugs, but by almost all measures it is my unprofessional opinion that amphetamines are worse than heroin.

First, heroin calms people down. They can be pretty bloody uncalm when they haven't got what they need, but somone withdrawing from H does not come into the ED and start swinging the fire extinguisher around by the hose and trash the place, after vigorously masturbating in the corner. No, that'd be that skinny guy on amphetamines last year.

Second, there is a limit to how much heroin you can take. Even if you have a tolerance like Keith's*, you don't get much more than six times a day. But the amphetamines - whatever you've got. Amphetamines you run until you run out.

Third, heroin depends on the vagaries of agriculture and the international situation. This means that there is a good chance that at some time, like now, the supply will become so damn crap that people will consider giving it up entirely. This is not likely to be the case for the amphetamines.

Lastly, and most nastily, you get most people, give them a heroin habit for ten or twenty years, at the end of that time they are pretty much the same person. Generally the same person a lot poorer, and more beaten about, somewhat the worse for wear for having to deal with some deeply nasty people who make their living selling the stuff, and almost always carrying some virological penalty from years of injecting - and a comparable psychological burden from the years of shame and hiding - but the same person. If they have managed to avoid a catastrophic overdose with the resultant frontal lobe damage, and Hep C, and HIV, and have managed to come unscathed through whatever it is they had to do to pay for what they used - then they are relatively okay.

But two years - hell, half a year - on amphetamines, a lot of people change. Ongoing heavy injecting amphetamine use, for even a few months - it changes people's brains in horrible ways.

Speed psychosis. Meth paranoia. Ice hallucinations. Those eyes that look everywhere, that hunching over, that horrible, low-grade, picric-acid "what the fuck you looking at?" state that's only ever one low syllable or sideways glance away from bone-breaking violence. Everyone who comes into the ED stabbed in a drug deal gone wrong - amphetamines. The woman's daughter the other day, the armed robber, held up eight service stations in two weeks - amphetamines. In close on a year I never ever saw a kid in Mauro or Stewart (the juvenile prisons) who hadn't been on amphetamines in the week they'd been arrested. This is the twelve year old rapists, the softly spoken murderers, the sweet teenaged girls who stabbed people. Amphetamines.

Anyway, awareness of this problem is growing. There was a horrific special on Four Corners the other month, the week Burian died - it was on the TV in the next room, wouldn't have known about it otherwise - explaining precisely how bad things were going to get how soon. The local yellow press have been mentioning it in their seven o'clock specials, a few columns in the White Australian, our national right wing rag... things are happening. The other day a doctor from Darwin rang me for advice about a fifteen year old Aboriginal boy on ice.

And I was thinking the other day about all the letters in the Sackbutt. Concerned businessmen, leadess of the chambers of commerce. Owners of car yards and television shops, restaurants and pubs. The exhaustive urine drug tests you have to go through to get a job at DT Breweries, the $50 000 of personal funds donated by one car salesman to a programme to keep kids off drugs, the demands pretty much everywhere for tougher penalties, longer sentences, bigger jails.

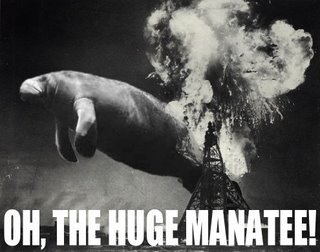

All of the pillars of society writing in. And I was thinking that I could discern barely concealed fear. As if we had heard traveller's tales, rumours, as if we had heard that fantastic and terrible beings were appearing on the fringes of our Empire

And I thought about what we have to offer, our society, the society built around the busnessmen whose advertisements and interviews and letters form so much of the Sackbutt, and who in the end pay my wages. I thought about the car, the house, the fine food, the pornshops and the bottleshops and the bookshops. The things our society offers those who forestall pleasure, delay gratification, pay the time and effort and money, do the right thing. Our rush, our drug, our high.

And I ran that through in my head against what ice can do. That neurochemically targetted supernova, that order of magnitude bigger and better and brighter thing, more than speeding in your Porsche at 300 kmh down an open highway, more than getting mindmeltingly good oral sex from an eastern European porn star at 300 kmh in a Porsche while downing fresh oysters by the gallon, washed down with ten thousand dollar Merlot.

Ice is easily made. The products cannot be anything but readily available. The knowledge is out there. And ice is only the current form - mutations, subtle variations are already appearing. The list of potential compounds is vast - while politicians thunder against what I could call "ice I", and announce laws that would impose heavy penalties for possession of any detectable amount of the dreaded substance, the more alert workers in the area are hearing about fucked up kids on something called "Ice V", and somewhere in a lab someone has just made "Ice IX".

We will never catch up. We never were close, but we're getting further and further behind - it is a brave person who speculates on the future of surveillance, but Benjamin Franklin said that the people who give up freedom for security deserve neither, and this stuff is being made in our neighbourhoods - so that's where we'll have to have the police with the ultrasensitive microphones and the infra-red cameras.

And someday soon there'll be something cheap and easily made that you can take just by touching it to your lips and it'll be better than anything you could ever work for, even if you worked all your life.

What then?

The unimaginable. How will our society, built on and by and largely for people who will accept delayed gratification of a certain, admittedly very nice level (show me those oysters again...) - how will that society compete with the offer of pleasure literally unimaginable, pleasure that compared to which everything else for ever after is tepid, pleasure that can be had for only a few dollars?

What then?

I feel sometimes we are like the Neandertals were, staring across the rift as another and yet another tribe of those skinny, unhealthy looking new people came along. Pale and ugly looking, but full of incomprehensible ideas - fantastic and terrible beings appearing on the fringes of our land, and feeling for the first time the vulnerability of our empire we thought would stand a thousand years.

Thanks for listening,

John

*Keith Richards. Will go to his grave having been the best white guitarist in the world. I don't know about a lot of the pharmaceutical stuff, but there are few non-synthetic pleasures that will ever rival being drunk and hearing those whispering drums at the start of Sympathy for the Devil.